The current exhibition Augustus John & the First Crisis of Brilliance at Piano Nobile (26 April-13 July 2024) gathers art made 1900-23 by artists associated with Bloomsbury, the Slade School of Drawing and the Cave of the Golden Calf. The Cave of the Golden Calf was a night club in central London that operated from 1912 to 1914 and hosted many leading avant-gardists of the day. (That link is not mentioned in the catalogue.) Of the exhibited artists, Augustus John, Gwen John, William Rothenstein, William Orpen, Derwent Lees, James Dickson Innes and Wyndham Lewis all studied at the Slade, only Jacob Epstein and Henry Lamb did not study at the Slade. At this time, these were the leading Modern artists in Great Britain, all living in London. This exhibition is reviewed from the catalogue.

Henry Tonks was Master of Drawing at the Slade and it was he who used the expression “crisis of brilliance” about a generation of his students who graduated in the 1890s.[i] These artists latched on the verve and virtuosity of Leonardo da Vinci, Anthony Van Dyck, Michelangelo and the early Venetians. Just as the Post-Impressionists and Fauves (and then later the Cubists) were conquering France, British artists were looking back to the Renaissance, hardly any different from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the 1840s, over half of a century earlier. And that, notwithstanding the brilliance of the individual artists exhibited here, is the main stumbling block to appreciating the British avant-garde before Vorticism. The comparison with the French and Germans – and let us not forget the Metaphysical art of Italian-Greek Giorgio de Chirico – the British look marvellously skilled but mired in fantasies centuries out of date. The Bloomsbury Group only look daring against the most polished of Victorian salon painters.

Does this exhibition, which includes museum loans as well as pieces from private collections, do anything to revise this perception of gifted retardataire artists reaching into the past to assert their independence of thought? Yes and no. Firstly, Lewis should separated from the rest of the group as he was a part of the Bloomsbury set briefly and his work is much more avowedly Modernist than theirs. His contribution to the exhibition is a robe with figural designs set in bands and lampshade designs for Omega Workshop (a short-lived association that ended in acrimony). A third piece is a unprepossessing portrait of Helen Saunders which he gave to the sitter, which has no exhibition history.

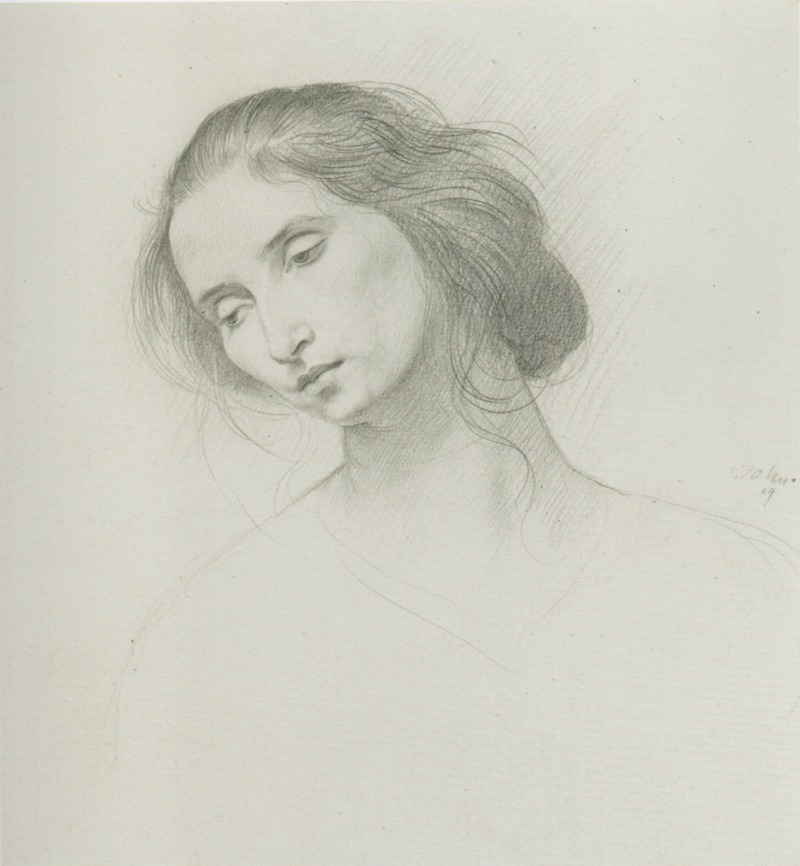

Augustus John came to venerate Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898) at about the time that painter was at the apex of his influence, in the decade following his death. Lewis felt that Augustus John dabbled (to his detriment) in a vast range of historical art styles. David Boyd Haycock notes in his diverting catalogue essay that Augustus John’s genius was held against him. It led people to expect greatness of everything he did. Certainly, Augustus John’s facility outshone his actual achievements. In fact, one could say that his genius was confined to the minor – the small portrait drawing – and did not extend to pieces that required more sustained thought or longer periods of execution. His larger figure compositions hold little interest for even positively-inclined viewers today and one has to make an effort to imagine the excitement they generated when first exhibited.

Haycock finds that Augustus John’s ability intimidated those around him and that Lewis may have turned to Cubism and Futurism precisely because he considered himself to compete with Augustus John in the field of realistic portrait and figure painting. Sickert believed that London artists had defected to foreign Modernism to escape the shadow of Augustus John. He defined the era, with artists emulating him or reacting against him, in much the same way as Picasso dominated the thinking of every young ambitious artist for half a century.

The portrait drawings feature important people in the artists’ lives, which overlapped. Augustus drew his lover Dorelia; Dorelia’s sister modelled for Lamb; Augustus and Orpen drew Ida (Augustus’s wife); Augustus drew Lewis, to whom he referred as a poet, because Lewis was too intimidated by Augustus to show him his art until he had become a Cubist; Epstein sculpted a bronze head of Augustus’s son; Lamb drew another of Augustus’s sons. Lamb’s wife Euphemia is drawn by him, Innes and Augustus and sculpted by Epstein; Lees’s wife is drawn by him and Augustus.

Many of the exhibition’s 45 items are small landscapes, painted en plein air in oil on panel, mostly during painting holidays in France, Wales and Ireland. This part of the show places the painters as part of the European mainstream. The style is Fauvist in its directness, though the colours are rarely that bright. All are painted in one sitting and have an attractive directness, which aligns them with the Canadian Modernists of the Group of Seven.

William Orpen’s brilliance as a draughtsman is confirmed here – a dangerous facility that made him able to bear all too readily the yoke of society portraiture. (Something that also hampered Augustus.) This fits firmly in the category of what I call Cosmopolitan Realism – bravura society figuration along the lines of Singer Sargent, Sorolla, Whistler and Zorn. A wonderful nude study of walking figures (shades of Masaccio’s Expulsion) for Orpen’s Nude Pattern: The Holy Well (1916) shows his mastery of anatomy. The drawing in question was given away in 1930, a year before the artist’s death.

The exhibition contains some wonderful finds to complement the staples, such as the acclaimed child’s head sculpted by Epstein, made in his early clean Modernist style, executed in 1907. Epstein’s other sculpture is a 1911 bronze bust of Euphemia, which seems (in illustration) handsome. Two very fine pencil drawings of her by Augustus and Lamb make one curious to see more portraits of her. The overall selection encourages us to become engaged with the lives of these subjects and their relationships with the artists. Generally wary of the biographical reading of art, I concede that it would make a very fertile subject for a large exhibition with catalogue. The recent collection of Ida’s letters was a step in the necessary research for such a project.

Henry Lamb emerges from the show looking a very skilled portraitist. Gwen John is represented by some female portraits and William Rothenstein by male portraits. There is intermittent excitement, a high level of accomplishment, some surprising and portraits that make us wish to know. One could hardly ask for more. A recommendation for those already interested in the group and for those keen on portraiture.

David Boyd Haycock, Augustus John & the First Crisis of Brilliance, Piano Nobile Publications, 2024, paperback, 128pp, £40

To read more articles by me and support my work by becoming a paid subscriber visit alexanderadamsart.substack.com

One thought on “Augustus John & the First Crisis of Brilliance”

Comments are closed.